You don’t get assassinated for preaching about love.

A Good Friday sermon in eight words.

But! It is the Easter season.

My technicolor hard-boiled eggs sit uneaten in the fridge (I’ll get to them…tomorrow) and our family has left town and I need to take a break from mimosas for a little while for reasons that should require no explanation.

It is the Easter season. Christ is risen.

It is the Easter season. Alleluias everywhere.

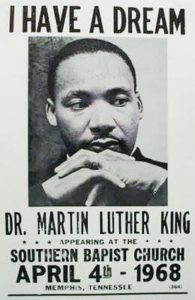

And today is April 4, 1968, and my call is calling me back to Good Friday.

(Except April 4, 1968, was a Thursday.

That’s okay: betrayal works too.)

You don’t get assassinated for preaching about love.

This is the conviction that lies underneath #whitechurchsilent. #whitechurchsilent is an online movement started in the wake of the 2016 election. It describes the phenomenon that occurs when pastors, leaders and congregations that are mostly white, that belong to mostly white denominations, that were started by white people, choose not to speak explicitly about the injustices and violence done to black and brown people in our neighborhoods and country.

Instead, we talk about love. Which is almost like not saying anything at all.

Which is why you don’t get assassinated for preaching about love.

Which is why I, and many of my pastor-preacher-minister-type colleagues are going to be just fine.

We’re safe.

We are safe when we are being called to be bold.

Like the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who was assassinated in Memphis on this day in 1968. For preaching about love–and how it cannot be decoupled from power and justice.

“We’ve worked hard to create a vision of King that is like a black Santa Claus,” says Charles McKinney, associate professor of history at Rhodes College. (I listened to his interview today on The Takeaway from WNYC; you can (and should) listen to it, too.) In other words, popular American culture memorializes Rev. King as someone who preached about love, and it has forgotten that he was called to Memphis to defend and affirm the lives of sanitation workers who were on strike, to challenge the city to give them a living wage. It was part of a campaign he was igniting to restructure the fabric of human life in the United States and to confront the reality of poverty.

You don’t get assassinated for preaching about love, remember?

Professor McKinney compares the popular culture version of Rev. King to Barney the Dinosaur singing “I love you, you love me”; he calls him “toothless.” He says we–and by “we” I mean corporate, political and religious forces who benefit (or at least remain safe) by promoting this sanitized version–have whittled Rev. King’s narrative down to one that is about love. The Hallmark kind. But the kind of love that King preached about was the kind of love that demanded we be in the streets; that demanded we work on behalf of and alongside the disinherited. It was the kind of love that got him killed.

So this is my commitment: to expand my imagination and my heart in ways that move me from safe to bold. To let you, my friends and neighbors, invite me into that transformation. It is not always easy to imagine what Rev. King’s work might look like in Central Oregon; at least three times a week someone tells me “how white” it is here. We can debate that informal (and changing) statistic, but the real question is: do we here in Oregon not still see the three main evils Rev. King was called to challenge?

Racism; militarism; poverty.

Those among us who are undocumented know these evils.

Those among us who are underemployed and unsafely housed know these evils.

How about #whitechurchbold?

How about #whitechurchlistening?

How about #whitechurchstandswith?

At Easter, I, alongside many others, celebrate the persistent life of the One who got assassinated for preaching about love that transforms the powers of the-world-as-it-is for the sake of justice on earth as it is in heaven.

May we listen to such bold calls and live by such bold examples.

Alleluia.

Everywhere.

– Erika

This is the third in our series on disrupting, reclaiming and expanding parts of Christian language, tradition and ritual for our lives and experiences here and now.

Recent Comments