First, I must confess that over the past few years I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate. I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to “order” than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says: “I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action”; who paternalistically believes he can set the timetable for another man’s freedom; who lives by a mythical concept of time and who constantly advises the Negro to wait for a “more convenient season.” Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection.

First, I must confess that over the past few years I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate. I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to “order” than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says: “I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action”; who paternalistically believes he can set the timetable for another man’s freedom; who lives by a mythical concept of time and who constantly advises the Negro to wait for a “more convenient season.” Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection.

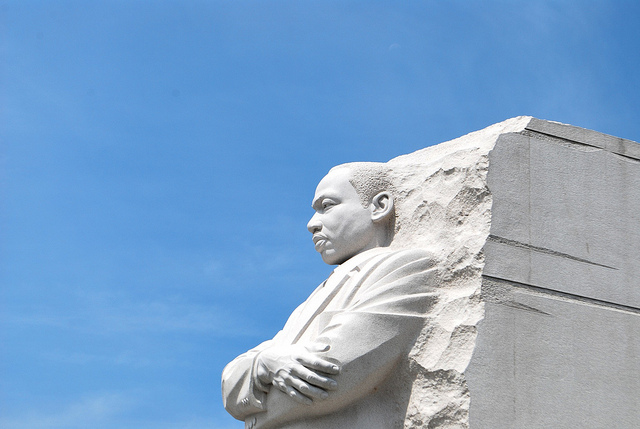

— Excerpt from Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s Letter from a Birmingham Jail

This letter has always been one of my scriptures: for the ways it makes me weep and holds a mirror to my face and invites me to gaze with love at our world.

Just as all good scriptures do.

I have beloveds who have lately said to me: “I want to be loving. I want to be compassionate. I want to transcend the lines that divide us–political, religious, ideological. But people keep disappointing me. They keep choosing compromise over me. They keep choosing religious doctrine over me. They keep choosing ‘peace’ over me.”

I invited our community to reflect this past weekend on where, how and with whom we are longing to “make room” for relationship. How our communal “womb” is invited to stretch and grow and be challenged for the sake of new life. I think it’s a good question: few of us can say we have learned to love others with perfect hospitality.

And yet: so many of us have already had to “make room.” To stand aside and let our relationships be more important than our pride, our dignity, our talents. We have already been making room for family members, colleagues, local governments, the wider culture to struggle with our sex or sexuality, our race, our age, our dreams and our visions. You name it, many of us have already learned to make room for it. Often, we have done it out of love. Often it is under duress and by force for the sake of survival.

I say “we” and “our” and yet am aware that Rev. King’s invitation is to me and folks like me: white, middle-class spiritual leaders. I weep when I read this letter, because that is the feeling of my womb being stretched. Room must be made in my mind, my actions, my energy, my body for the humanity and freedom of every single one of my sacred siblings.

Because we are accountable to our relationships. We (particularly people with power/privilege) can say or think or tweet or behave or vote or pray however we want, but we cannot do it without expecting some relational consequences. There is a line.

It need not divide us forever, it need not dismiss someone or banish them outside of a community or a circle or from our lives entirely. For what it’s worth, my theology, my Bible and my relationship with the Holy do not send folks to an afterlife hell.

But we must ask, expect and–when the time comes–require from our relationships speech, actions, and behavior that are loving, respectful and humanizing. And, dare I say, awe-filled. We are invited to be in awe of one another by the Spirit who dwells within each of us.

So, yeah, there’s a line.

Among the community that is becoming Story Dwelling, we have that kind of line. We expect justice-love from one another. We will not engage in debate about whether someone is fully human, fully beloved, fully justified (to use that oh-so-religious word). That means LGBTQ+ folx are not “them”–”they” are us. Leaders. Organizers. Collaborators. That means women and people of color and young people and immigrants and refugees are not “them”– “they” are us. We will not debate our marriages, our leadership, our giftedness. We may experience tension about how best to strategize; we may realize we have messed up and forgotten to invite someone to the table; we may struggle with our own feelings of guilt that come with privilege or feelings of inadequacy that come with oppression. We will struggle with those things. But we will not debate our worth or our liberation destiny. That is not what beloved community does. The same good reverend whose life we celebrate today teaches us that.

There is a line. It need not separate us. But it does need to be a loving boundary–a trustworthy, hospitable and strong-as-hell container–that allows for vulnerability and deep belonging and loving story-telling. We deserve that kind of womb, and our neighborhoods deserve faith communities that respond to that sense of belonging by working, pushing, conspiring– until all belong.

Recent Comments